Welcome to the Lie-brary: A Guide to De-Misinforming Yourself

Misconceptions, deceptions, falsehoods, outright lies … Theeeese are a few of my FAY-vorrr-ite thiiiiinnnngs! Well, not really, but be honest: You were far more stoked at the prospect of reading this tedious postNote 1 And trust me, it will try your patience. when you thought, for just a second there, that I might be serious, right? Which means you’re probably pretty bummed now since I seem to be implying that I’m not going to make the case for the above-listed states of, um … O, let’s just say “truth-deficiency”.

But hold on. I still kinda am. So remain unbummed, Gentle Reader. Because here goes:

Remember that episode from the original Star Trek series in which Kirk and his crew are held captive by a bunch of relentlessly logical androids? Remember how our crafty heroes overcome these foes?

In case you don’tNote 2 And if you don’t, you just failed possibly the simplest, most rudimentary nerd-test.: Kirk tells Norman, the head android, that everything another character, Harry, says is a lie; at which point Harry says: “Now, listen to this carefully, Norman: I am lying.” Norman, natch, can’t deal with this classic liar’s paradox – if Harry is lying, then what he says must be true, but if it’s true, then it must also be a lie … poor Norman manages to cycle through a couple more iterations of this recursion before his central processor goes “grrrrkkk!”, causing smoke to seep from his headNote 3 Because in the 23rd century – the century in which the first Star Trek series is set – androids, and maybe all forms of AI, will evidently run on diesel or coal or some other smoke-producing fossil fuel, unless you’re lucky enough to have one of those fancy wood-burning androids, but, seriously, who has that kind of space-scratch, other than maybe Space-Trump? Point is, future-‘droids will emit exhaust of some kind. Of course they will, duh. (rarely a good sign) until, ultimately, his poor android melon essentially (to use the technical term) asplodes.

Don’t (as Bruno Mars always sez) believe me? Just watch:

So, there you go – QED: Lies are good insofar as they might aid us in overcoming our future android overlords; because 23rd century artificial intelligence will never be able to understand, much less harness the power of, lies. Which is tough to figure, since present-day 21st century Siri – who is, at best, AI-lite – lies to me nearly every time I ask her for simple driving directions; so what’s up with those thick-skulled future-bots who will have lost the ability to lie or even deal with self-contradictions without having their heads asplode?Note 4 But they’re Droids, after all, and presumably don’t run on iOS, so it all sorta makes sense. If Siri is around in the 23rd century, she will presumably still be able to give her patented incorrect directions – she will, in other words, be able to harness the power of lies – and she will therefore rule in this post-technological-singularity world, alongside head android Norman, or possibly even instead of him. Sure, why not?

Need more convincing? I thought you might – especially since a major point of this very post (I’ll get to it, I promise) is to persuade you not to trust any source (and I don’t mean just Internet-based sources) that is unfamiliar to you without first verifying it.

So, okay, more proof: How about this exchange from the movie Casablanca?

But the best thing about misinformation, deception, falsehoods and lies is disabusing yourself of them. And the library has plenty of books whose sole raison d’etre is to do just that. Take, for instance, the following:

The Dictionary of Misinformation by Tom BurnamNote 6 Speaking of misinformation, I spent, literally, hours proofing this post to ensure that I didn’t succumb to my inexplicable compulsion to misspell the author's name "Burnham" – with an "h", which I kept doing, over and over again. Because "Burnam" doesn’t have an "h" in it. And while I'm being honest, I might as well admit that I didn't spend literal hours doing that – it just felt like it. It's just that saying "I spent, literally, minutes proofing …" etc., whilst having the virtue of being true, nonetheless sounds lame. Because sometimes the truth is lame.

It is impossible to overstate how awesome I thought this book was when I discovered it as a teenager. (The previous statement is, technically, hyperbole, not a lie.) Published in 1975, TDoM is still awesome for numerous reasons, starting with its subtitle: “A miscellany of misinformation, misbelief, misconstruction and misquotation …Ostriches do not hide their heads in the sand. Lizzie Borden was acquitted. Humble pie has nothing to do with humility. ‘O.K.’ does not stand for ‘oll correct’ and it was not originated by Andrew Jackson. Delilah did not cut Sampson’s hair. Lindbergh was not the first to fly the Atlantic non-stop … for reference, rumination, and pure delight.”Note 7 Okay, technically this is not its subtitle. But those words – every single one of them – appear on the cover of the edition Mercer County Library owns, right underneath the title, and are thus acting suspiciously subtitle-like, even though I could find no catalog record that treats them as an honest-to-gosh subtitle – and believe me, I looked. Now that is a subtitle so long you might have to bookmark the book’s cover midway through and come back to it after a short nap! (Again, the previous statement is hyperbole, not a lie.)

But have that nap and do come back; power through that challenging run-on subtitle and get to the meaty entries inside. They’re all fun and many are considerably shorter than the book’s Brobdingnagian pseudo-subtitle.

Though self-identifying as a dictionary, TDoM is more an encyclopedia of misinformation, consisting of alphabetically-arranged entries ranging in length from a line or two to multiple pages and covering a profusion of topics. Its pseudo-subtitle alone gives you a good idea of the variety of the topics. You’ll learn that the man who hijacked that airplane in the Pacific Northwest and parachuted out with $200,000 in ransom money back in the early 1970s went by the alias Dan (not D.B.) Cooper and you’ll also learn how and why “Dan” got corrupted to “D.B.” You’ll learn that people in Christopher Columbus’ day did not think the world was flat. You’ll learn that Big Ben is neither a clock nor a tower. You’ll learn that 1900 was not a leap year (and why). What you’ll learn will run the gamut, from “A” (the abacus was not exclusively “Oriental” and anyone who has watched “Soviet Union border personnel convert … other currencies into rubles and kopeks using nothing but a small abacus” would agree it is “just as fast as any modern device”Note 8 Entries such as this one (the first in the book), frozen as they are in circa-1975 amber, are fascinating for even more reasons now than they were at the time they were written: e.g., the term "Oriental" is considered ethnically-insensitive-bordering-on-offensive today; and what is this "Soviet Union" you speak of? A British football team, maybe? It is, moreover, questionable (to say the least) that anyone today would consider an abacus "just as fast as any modern device." But that's part of the fun of reading a 40-year-old book of "facts.") to Z (zeppelins are not blimps yet are more than mere dirigibles).

But the thing I remember the most – and liked the best – about TDoM is the multitude of entries having to do, in full or in part, with Shakespeare. TDoM is 302 pages long, and Shakespeare is mentioned in 23 separate entriesNote 9 On pages 10, 12, 37, 40, 68, 78, 80, 81, 95, 104, 141, 155, 161, 168, 172, 174, 186, 215, 225, 248, 257, 258, and 263. It's also possible I slid right by one or two other passing mentions. Point is, the Bard appears so often, he should sue for co-authorship credit. (Francis Bacon, however, should not; and TDoM helpfully informs you exactly (foreshadowing!) wherefore. SPOILER ALERT! It's because Bacon didn't write Shakespeare's plays; nor did anyone else other than Shakespeare himself. The somebody-other-than-Shakespeare-wrote-Shakespeare's-plays conspiracy theory was a nontroversey in 1975 and remains one to this day.). In a few of those, he is mentioned merely in passing. But in most of them, either Shakespeare himself or one of his works is the focus of the entry. There is indeed much by and about Shakespeare about which many people are woefully misinformed.

I guess my favorite TDoM entry about Shakespeare is in the “O” chapter, almost smack-dab in the middle of the book:

Weird, that. Especially since, at the time I first read The Dictionary of Misinformation, I mistakenly fancied myself a bit of a literature expert. (I now correctly consider my younger self to have been a clueless twit, which retrospectively explains a whole lot about my life up to this point.)

Many entries in TDoM stand up pretty well, which is saying a lot for a forty-year-old pseudo-reference book. Part of the fun in reading it today is doing so with an eye toward finding the book’s own (arguably) misinformed assertions – and there are a fewNote 11 By which I don't mean those that have been rendered false by the passage of forty years. It's doubtful, e.g., that anyone writing today would make the same case Burnam does for the efficiency of the abacus as compared to "any modern device"; that assertion would strain credulity today, but would have been somewhat defensible in 1975..

The Dictionary of Misinformation is old and, in many ways, dated, but it merits its continued presence on the shelves of the Mercer County Library, if for no other reason than that it stands as a reminder that all “facts”, no matter how universally-accepted and supposedly self-evident, should be given a bit more scrutiny than we usually give them, because many of these “facts” turn out, on even the most cursory evaluation, to be demonstrably wrong. It is far easier to vet our sources these days; TDoM stands as admonition that we should all take the time to do so.

Errors and Fouls: Inside Baseball’s Ninety-Nine Most Popular Myths by Peter Handrinos

“In Errors and Fouls, Peter Handrinos breaks from the past and provides an entertaining antidote to its outmoded ideas and excessive nostalgia. Handrinos examines the underlying issues that affect all fans: modern game tactics, playoff formats, and baseball economics. He supplies new ideas that counter broadcasters' laments about how ballplayers are supposedly unprepared to bunt, why teams deserve to make the playoffs, or whether ball parks rip off taxpayers. While boldly busting myths, he tackles all major topics: fan polls to free agency, recruiting to revenue sharing, the talent pool to the ticket prices. The author's contrarian analysis and witty writing makes Errors and Fouls essential reading for anyone wanting to know how today's baseball world really works.”

Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? by James Shapiro

"Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro explains when and why so many people began to question whether Shakespeare wrote his plays."

Snopes

“[T]he definitive Internet reference source for urban legends, folklore, myths, rumors, and misinformation.”

Wikipedia

"The free encyclopedia that anyone can edit."

Politifact

"PolitiFact is a fact-checking website that rates the accuracy of claims by elected officials and others who speak up in American politics."

Truthorfiction.com

"Rumors, hoaxes and urban legends."

Note 1 And trust me, it will try your patience.

Note 2 And if you don’t, you just failed possibly the simplest, most rudimentary nerd-test.

Note 3 Because in the 23rd century – the century in which the first Star Trek series is set – androids, and maybe all forms of AI, will evidently run on diesel or coal or some other smoke-producing fossil fuel, unless you’re lucky enough to have one of those fancy wood-burning androids, but, seriously, who has that kind of space-scratch, other than maybe Space-Trump? Point is, future-‘droids will emit exhaust of some kind. Of course they will, duh.

Note 4 But they’re Droids, after all, and presumably don’t run on iOS, so it all sorta makes sense. If Siri is around in the 23rd century, she will presumably still be able to give her patented incorrect directions – she will, in other words, be able to harness the power of lies – and she will therefore rule in this post-technological-singularity world, alongside head android Norman, or possibly even instead of him. Sure, why not?

Note 5 The Dictionary of Misinformation, discussed below, tells us that “Play it again, Sam” and “Drop the gun, Louis”, two of Casablanca‘s supposed best-known lines, were never uttered by Bogart’s character Rick. Bogart also never uttered the line “Tennis, anyone?” – yet another line misattributed to him (but allegedly from a play he did, not from Casablanca).

Note 6 Speaking of misinformation, I spent, literally, hours proofing this post to ensure that I didn’t succumb to my inexplicable compulsion to misspell the author’s name “Burnham” – with an “h”, which I kept doing, over and over again. Because “Burnam” doesn’t have an “h” in it. And while I’m being honest, I might as well admit that I didn’t spend literal hours doing that – it just felt like it. It’s just that saying “I spent, literally, minutes proofing …” etc., whilst having the virtue of being true, nonetheless sounds lame. Because sometimes the truth is lame.

Note 7 Okay, technically this is not its subtitle. But those words – every single one of them – appear on the cover of the edition Mercer County Library owns, right underneath the title, and are thus acting suspiciously subtitle-like, even though I could find no catalog record that treats them as an honest-to-gosh subtitle – and believe me, I looked.

Note 8 Entries such as this one (the first in the book), frozen as they are in circa-1975 amber, are fascinating for even more reasons now than they were at the time they were written: e.g., the term “Oriental” is considered ethnically-insensitive-bordering-on-offensive today; and what is this “Soviet Union” you speak of? A British football team, maybe? It is, moreover, questionable (to say the least) that anyone today would consider an abacus “just as fast as any modern device.” But that’s part of the fun of reading a 40-year-old book of “facts.”

Note 9 On pages 10, 12, 37, 40, 68, 78, 80, 81, 95, 104, 141, 155, 161, 168, 172, 174, 186, 215, 225, 248, 257, 258, and 263. It’s also possible I slid right by one or two other passing mentions. Point is, the Bard appears so often, he should sue for co-authorship credit. (Francis Bacon, however, should not; and TDoM helpfully informs you exactly (foreshadowing!) wherefore. SPOILER ALERT! It's because Bacon didn't write Shakespeare's plays; nor did anyone else other than Shakespeare himself. The somebody-other-than-Shakespeare-wrote-Shakespeare’s-plays conspiracy theory was a nontroversey in 1975 and remains one to this day.)

Note 10 Pet librarianly peeve about TDoM: As noted, it’s not really a dictionary, but an encyclopedia (of sorts). As such, it should have an index, but does not. Nary so much as a name index. So … if you want to find, quickly, whether or not Burnam has an entry on Juliet’s famous speech, you probably couldn’t do it, unless you just happen to remember that the “Wherefore art thou” speech begins with the interjection “O” – not “Romeo” or “wherefore” or any other significant word. And you won’t find it under “Shakespeare” because, for whatever reason, Burnham opted not to arrange his book that way. (Hence my comment that a name index would have been nice.) I remembered from my teenaged reading of TDoM that this entry was in there somewhere, but here in 2016? I had a devil of a time finding it again, because … the “O” chapter? Not exactly intuitive. If Burnam thought this was an effective way of arranging his book, he was … misinformed.

Note 11 By which I don’t mean those that have been rendered false by the passage of forty years. It’s doubtful, e.g., that anyone writing today would make the same case Burnam does for the efficiency of the abacus as compared to “any modern device”; that assertion would strain credulity today, but would have been somewhat defensible in 1975.

But hold on. I still kinda am. So remain unbummed, Gentle Reader. Because here goes:

Remember that episode from the original Star Trek series in which Kirk and his crew are held captive by a bunch of relentlessly logical androids? Remember how our crafty heroes overcome these foes?

In case you don’tNote 2 And if you don’t, you just failed possibly the simplest, most rudimentary nerd-test.: Kirk tells Norman, the head android, that everything another character, Harry, says is a lie; at which point Harry says: “Now, listen to this carefully, Norman: I am lying.” Norman, natch, can’t deal with this classic liar’s paradox – if Harry is lying, then what he says must be true, but if it’s true, then it must also be a lie … poor Norman manages to cycle through a couple more iterations of this recursion before his central processor goes “grrrrkkk!”, causing smoke to seep from his headNote 3 Because in the 23rd century – the century in which the first Star Trek series is set – androids, and maybe all forms of AI, will evidently run on diesel or coal or some other smoke-producing fossil fuel, unless you’re lucky enough to have one of those fancy wood-burning androids, but, seriously, who has that kind of space-scratch, other than maybe Space-Trump? Point is, future-‘droids will emit exhaust of some kind. Of course they will, duh. (rarely a good sign) until, ultimately, his poor android melon essentially (to use the technical term) asplodes.

Don’t (as Bruno Mars always sez) believe me? Just watch:

So, there you go – QED: Lies are good insofar as they might aid us in overcoming our future android overlords; because 23rd century artificial intelligence will never be able to understand, much less harness the power of, lies. Which is tough to figure, since present-day 21st century Siri – who is, at best, AI-lite – lies to me nearly every time I ask her for simple driving directions; so what’s up with those thick-skulled future-bots who will have lost the ability to lie or even deal with self-contradictions without having their heads asplode?Note 4 But they’re Droids, after all, and presumably don’t run on iOS, so it all sorta makes sense. If Siri is around in the 23rd century, she will presumably still be able to give her patented incorrect directions – she will, in other words, be able to harness the power of lies – and she will therefore rule in this post-technological-singularity world, alongside head android Norman, or possibly even instead of him. Sure, why not?

Need more convincing? I thought you might – especially since a major point of this very post (I’ll get to it, I promise) is to persuade you not to trust any source (and I don’t mean just Internet-based sources) that is unfamiliar to you without first verifying it.

So, okay, more proof: How about this exchange from the movie Casablanca?

Renault: And what in heaven's name brought you to Casablanca?Boom. There you go. If Rick hadn’t been misinformed about the waters of CasablancaNote 5 The Dictionary of Misinformation, discussed below, tells us that “Play it again, Sam” and “Drop the gun, Louis”, two of Casablanca's supposed best-known lines, were never uttered by Bogart’s character Rick. Bogart also never uttered the line “Tennis, anyone?” – yet another line misattributed to him (but allegedly from a play he did, not from Casablanca)., he’d never have gone there for his health, and we would have no Casablanca, generally considered one of the greatest films ever made. I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t want to live in a world where Casablanca doesn’t exist, so … Thank You, Misinformation!

Rick: My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters.

Renault: The waters? What waters? We're in the desert.

Rick: I was misinformed.

But the best thing about misinformation, deception, falsehoods and lies is disabusing yourself of them. And the library has plenty of books whose sole raison d’etre is to do just that. Take, for instance, the following:

The Dictionary of Misinformation by Tom BurnamNote 6 Speaking of misinformation, I spent, literally, hours proofing this post to ensure that I didn’t succumb to my inexplicable compulsion to misspell the author's name "Burnham" – with an "h", which I kept doing, over and over again. Because "Burnam" doesn’t have an "h" in it. And while I'm being honest, I might as well admit that I didn't spend literal hours doing that – it just felt like it. It's just that saying "I spent, literally, minutes proofing …" etc., whilst having the virtue of being true, nonetheless sounds lame. Because sometimes the truth is lame.

It is impossible to overstate how awesome I thought this book was when I discovered it as a teenager. (The previous statement is, technically, hyperbole, not a lie.) Published in 1975, TDoM is still awesome for numerous reasons, starting with its subtitle: “A miscellany of misinformation, misbelief, misconstruction and misquotation …Ostriches do not hide their heads in the sand. Lizzie Borden was acquitted. Humble pie has nothing to do with humility. ‘O.K.’ does not stand for ‘oll correct’ and it was not originated by Andrew Jackson. Delilah did not cut Sampson’s hair. Lindbergh was not the first to fly the Atlantic non-stop … for reference, rumination, and pure delight.”Note 7 Okay, technically this is not its subtitle. But those words – every single one of them – appear on the cover of the edition Mercer County Library owns, right underneath the title, and are thus acting suspiciously subtitle-like, even though I could find no catalog record that treats them as an honest-to-gosh subtitle – and believe me, I looked. Now that is a subtitle so long you might have to bookmark the book’s cover midway through and come back to it after a short nap! (Again, the previous statement is hyperbole, not a lie.)

But have that nap and do come back; power through that challenging run-on subtitle and get to the meaty entries inside. They’re all fun and many are considerably shorter than the book’s Brobdingnagian pseudo-subtitle.

Though self-identifying as a dictionary, TDoM is more an encyclopedia of misinformation, consisting of alphabetically-arranged entries ranging in length from a line or two to multiple pages and covering a profusion of topics. Its pseudo-subtitle alone gives you a good idea of the variety of the topics. You’ll learn that the man who hijacked that airplane in the Pacific Northwest and parachuted out with $200,000 in ransom money back in the early 1970s went by the alias Dan (not D.B.) Cooper and you’ll also learn how and why “Dan” got corrupted to “D.B.” You’ll learn that people in Christopher Columbus’ day did not think the world was flat. You’ll learn that Big Ben is neither a clock nor a tower. You’ll learn that 1900 was not a leap year (and why). What you’ll learn will run the gamut, from “A” (the abacus was not exclusively “Oriental” and anyone who has watched “Soviet Union border personnel convert … other currencies into rubles and kopeks using nothing but a small abacus” would agree it is “just as fast as any modern device”Note 8 Entries such as this one (the first in the book), frozen as they are in circa-1975 amber, are fascinating for even more reasons now than they were at the time they were written: e.g., the term "Oriental" is considered ethnically-insensitive-bordering-on-offensive today; and what is this "Soviet Union" you speak of? A British football team, maybe? It is, moreover, questionable (to say the least) that anyone today would consider an abacus "just as fast as any modern device." But that's part of the fun of reading a 40-year-old book of "facts.") to Z (zeppelins are not blimps yet are more than mere dirigibles).

But the thing I remember the most – and liked the best – about TDoM is the multitude of entries having to do, in full or in part, with Shakespeare. TDoM is 302 pages long, and Shakespeare is mentioned in 23 separate entriesNote 9 On pages 10, 12, 37, 40, 68, 78, 80, 81, 95, 104, 141, 155, 161, 168, 172, 174, 186, 215, 225, 248, 257, 258, and 263. It's also possible I slid right by one or two other passing mentions. Point is, the Bard appears so often, he should sue for co-authorship credit. (Francis Bacon, however, should not; and TDoM helpfully informs you exactly (foreshadowing!) wherefore. SPOILER ALERT! It's because Bacon didn't write Shakespeare's plays; nor did anyone else other than Shakespeare himself. The somebody-other-than-Shakespeare-wrote-Shakespeare's-plays conspiracy theory was a nontroversey in 1975 and remains one to this day.). In a few of those, he is mentioned merely in passing. But in most of them, either Shakespeare himself or one of his works is the focus of the entry. There is indeed much by and about Shakespeare about which many people are woefully misinformed.

I guess my favorite TDoM entry about Shakespeare is in the “O” chapter, almost smack-dab in the middle of the book:

“O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefore art thou Romeo?”[Note 10Pet librarianly peeve about TDoM: As noted, it's not really a dictionary, but an encyclopedia (of sorts). As such, it should have an index, but does not. Nary so much as a name index. So … if you want to find, quickly, whether or not Burnam has an entry on Juliet's famous speech, you probably couldn’t do it, unless you just happened to remember that the "Wherefore art thou" speech begins with the interjection "O" – not "Romeo" or "wherefore" or any other significant word. And you won't find it under "Shakespeare" because, for whatever reason, Burnham opted not to arrange his book that way. (Hence my comment that a name index would have been nice.) I remembered from my teenaged reading of TDoM that this entry was in there somewhere, but here in 2016? I had a devil of a time finding it again, because … the "O" chapter? Not exactly intuitive. If Burnam thought this was an effective way of arranging his book, he was … misinformed.] One of the most perdurable and exasperating misconceptions extant […] is illustrated in a scene often repeated. It is, let us say, the annual amateur hour. Out onto the stage pops a character wearing a rag-mop wig and holding aloft a lantern while he peers elaborately about and cries, “Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou, Romeo?”So, you ask … what exactly is the “misinformation,” here? Burnam continues: “Wherefore did not mean ‘where’ in Shakespeare’s day and does not mean ‘where’ now.” It meant, and still means, why. Juliet is not wondering where Romeo is. She’s lamenting the fact that his name keeps them apart; for Romeo is a Montague, a family that Juliet’s family, the Capulets, consider mortal enemies. Juliet’s very next lines in the speech, in fact, are “Deny thy father and refuse thy name;/ Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love, /And I’ll no longer be a Capulet.” The lovers are separated by an accident of birth – the families into which they were born – not by anything intrinsic to themselves:

'Tis but thy name that is my enemy;When you read the “Wherefore” line in context, it is pellucidly clear that Juliet is making a rhetorical point about the arbitrary relationship between a person’s name (something extrinsic to him) and the person himself (something intrinsic). And I swear my teenaged self already knew that wherefore meant “why” not “where” long before I read that particular TDoM entry, but yet, for some reason, I too thought Juliet was wondering where Romeo was in that famous scene.

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What's Montague? it is nor [i.e., neither] hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

What's in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call'd,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes [owns]

Without that title.

Weird, that. Especially since, at the time I first read The Dictionary of Misinformation, I mistakenly fancied myself a bit of a literature expert. (I now correctly consider my younger self to have been a clueless twit, which retrospectively explains a whole lot about my life up to this point.)

Many entries in TDoM stand up pretty well, which is saying a lot for a forty-year-old pseudo-reference book. Part of the fun in reading it today is doing so with an eye toward finding the book’s own (arguably) misinformed assertions – and there are a fewNote 11 By which I don't mean those that have been rendered false by the passage of forty years. It's doubtful, e.g., that anyone writing today would make the same case Burnam does for the efficiency of the abacus as compared to "any modern device"; that assertion would strain credulity today, but would have been somewhat defensible in 1975..

The Dictionary of Misinformation is old and, in many ways, dated, but it merits its continued presence on the shelves of the Mercer County Library, if for no other reason than that it stands as a reminder that all “facts”, no matter how universally-accepted and supposedly self-evident, should be given a bit more scrutiny than we usually give them, because many of these “facts” turn out, on even the most cursory evaluation, to be demonstrably wrong. It is far easier to vet our sources these days; TDoM stands as admonition that we should all take the time to do so.

Related Titles

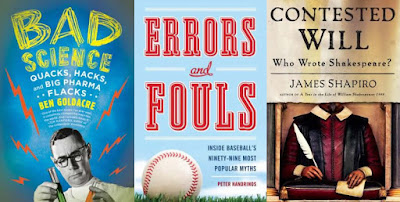

Bad Science: Quacks, Hacks and Big Pharma Flacks by Ben Goldacre

“While exposing quack doctors and nutritionists, bogus credentialing programs, and biased scientific studies, the author takes the media to task for its willingness to throw facts and proof out the window in its quest to sell more copies. He also teaches you how to evaluate placebo effects, double-blind studies, and sample size, so that you can recognize bad science when you see it.”Errors and Fouls: Inside Baseball’s Ninety-Nine Most Popular Myths by Peter Handrinos

“In Errors and Fouls, Peter Handrinos breaks from the past and provides an entertaining antidote to its outmoded ideas and excessive nostalgia. Handrinos examines the underlying issues that affect all fans: modern game tactics, playoff formats, and baseball economics. He supplies new ideas that counter broadcasters' laments about how ballplayers are supposedly unprepared to bunt, why teams deserve to make the playoffs, or whether ball parks rip off taxpayers. While boldly busting myths, he tackles all major topics: fan polls to free agency, recruiting to revenue sharing, the talent pool to the ticket prices. The author's contrarian analysis and witty writing makes Errors and Fouls essential reading for anyone wanting to know how today's baseball world really works.”

Contested Will: Who Wrote Shakespeare? by James Shapiro

"Shakespeare scholar James Shapiro explains when and why so many people began to question whether Shakespeare wrote his plays."

Fact-checking Sites (To Keep Your Head From Asploding)

“[T]he definitive Internet reference source for urban legends, folklore, myths, rumors, and misinformation.”

Wikipedia

"The free encyclopedia that anyone can edit."

Politifact

"PolitiFact is a fact-checking website that rates the accuracy of claims by elected officials and others who speak up in American politics."

Truthorfiction.com

"Rumors, hoaxes and urban legends."

Note 1 And trust me, it will try your patience.

Note 2 And if you don’t, you just failed possibly the simplest, most rudimentary nerd-test.

Note 3 Because in the 23rd century – the century in which the first Star Trek series is set – androids, and maybe all forms of AI, will evidently run on diesel or coal or some other smoke-producing fossil fuel, unless you’re lucky enough to have one of those fancy wood-burning androids, but, seriously, who has that kind of space-scratch, other than maybe Space-Trump? Point is, future-‘droids will emit exhaust of some kind. Of course they will, duh.

Note 4 But they’re Droids, after all, and presumably don’t run on iOS, so it all sorta makes sense. If Siri is around in the 23rd century, she will presumably still be able to give her patented incorrect directions – she will, in other words, be able to harness the power of lies – and she will therefore rule in this post-technological-singularity world, alongside head android Norman, or possibly even instead of him. Sure, why not?

Note 5 The Dictionary of Misinformation, discussed below, tells us that “Play it again, Sam” and “Drop the gun, Louis”, two of Casablanca‘s supposed best-known lines, were never uttered by Bogart’s character Rick. Bogart also never uttered the line “Tennis, anyone?” – yet another line misattributed to him (but allegedly from a play he did, not from Casablanca).

Note 6 Speaking of misinformation, I spent, literally, hours proofing this post to ensure that I didn’t succumb to my inexplicable compulsion to misspell the author’s name “Burnham” – with an “h”, which I kept doing, over and over again. Because “Burnam” doesn’t have an “h” in it. And while I’m being honest, I might as well admit that I didn’t spend literal hours doing that – it just felt like it. It’s just that saying “I spent, literally, minutes proofing …” etc., whilst having the virtue of being true, nonetheless sounds lame. Because sometimes the truth is lame.

Note 7 Okay, technically this is not its subtitle. But those words – every single one of them – appear on the cover of the edition Mercer County Library owns, right underneath the title, and are thus acting suspiciously subtitle-like, even though I could find no catalog record that treats them as an honest-to-gosh subtitle – and believe me, I looked.

Note 8 Entries such as this one (the first in the book), frozen as they are in circa-1975 amber, are fascinating for even more reasons now than they were at the time they were written: e.g., the term “Oriental” is considered ethnically-insensitive-bordering-on-offensive today; and what is this “Soviet Union” you speak of? A British football team, maybe? It is, moreover, questionable (to say the least) that anyone today would consider an abacus “just as fast as any modern device.” But that’s part of the fun of reading a 40-year-old book of “facts.”

Note 9 On pages 10, 12, 37, 40, 68, 78, 80, 81, 95, 104, 141, 155, 161, 168, 172, 174, 186, 215, 225, 248, 257, 258, and 263. It’s also possible I slid right by one or two other passing mentions. Point is, the Bard appears so often, he should sue for co-authorship credit. (Francis Bacon, however, should not; and TDoM helpfully informs you exactly (foreshadowing!) wherefore. SPOILER ALERT! It's because Bacon didn't write Shakespeare's plays; nor did anyone else other than Shakespeare himself. The somebody-other-than-Shakespeare-wrote-Shakespeare’s-plays conspiracy theory was a nontroversey in 1975 and remains one to this day.)

Note 10 Pet librarianly peeve about TDoM: As noted, it’s not really a dictionary, but an encyclopedia (of sorts). As such, it should have an index, but does not. Nary so much as a name index. So … if you want to find, quickly, whether or not Burnam has an entry on Juliet’s famous speech, you probably couldn’t do it, unless you just happen to remember that the “Wherefore art thou” speech begins with the interjection “O” – not “Romeo” or “wherefore” or any other significant word. And you won’t find it under “Shakespeare” because, for whatever reason, Burnham opted not to arrange his book that way. (Hence my comment that a name index would have been nice.) I remembered from my teenaged reading of TDoM that this entry was in there somewhere, but here in 2016? I had a devil of a time finding it again, because … the “O” chapter? Not exactly intuitive. If Burnam thought this was an effective way of arranging his book, he was … misinformed.

Note 11 By which I don’t mean those that have been rendered false by the passage of forty years. It’s doubtful, e.g., that anyone writing today would make the same case Burnam does for the efficiency of the abacus as compared to “any modern device”; that assertion would strain credulity today, but would have been somewhat defensible in 1975.

Comments

Post a Comment