Some Animadversions Concerning Grammar Fascism

Way back in 2003, a British publisher—Profile Books, Ltd.—issued a book titled Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation by one Lynne Truss; the book became so inexplicably popular on John Bull’s island that, in 2004, Gotham Books, an imprint of Penguin, published an edition for us here in the colonies that also became a number one bestseller.

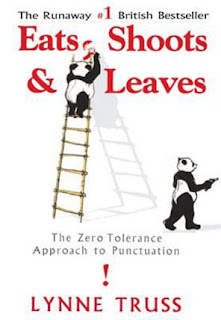

Eats, Shoots & Leaves is the book’s official title, though it should be noted that its jacket (left) depicts a panda on a ladder assiduously painting over the titular comma while another panda (or the same one, moments later?) with a gun walks off, stage-left—a visual depiction of the comma-laden meaning of the title. That comma’s presence or absence matters for purposes of meaning-interpretation; and the difference in meaning between the comma-laden version of the phrase and the comma-free version serves as rationale for the existence of the book itself. Without the comma, the phrase might refer to the fact that a panda “eats [bamboo] shoots and [various types of tree and plant] leaves” while, with the comma, the title might be alluding to the fact that a panda with a gun does just about anything it wants, but, most relevantly to the book’s title, it “eats [perhaps some yummy bamboo], shoots [a gun, presumably, but let us Pollyanna-ishly assume it fires that gun harmlessly into the air to celebrate how yummy those bamboo shoots were] and [then] leaves [before, say, the panda cops arrive, ask what all the shooting's about and start indiscriminately tasering panda-folk].” Point is, the comma—that seemingly insignificant punctuation mark—makes a big difference in how to interpret that phrase. Bestsellers have been constructed around less earth-shattering insights, I suppose, but I can't think of any examples offhand, so maybe not.

O, and also? The subtitle on the book’s cover is followed by a GIANT RED EXCLAMATION POINT!, which, yeah, I have no idea what that's all about. Seems gratuitous, which is odd for a book whose whole premise is that accurate punctuation matters.

Why a book “aimed at the tiny minority of British people ‘who love punctuation and don’t like to see it mucked about with’” should become a bestseller in Britain, much less in America, was then, and remains today, difficult to fathom. But bestsell it did—on both sides of The Pond.

When I deem the book’s popularity “inexplicable”, I am not being cruel or judgmental or—Heaven forfend!—cruelly judgmental; I am, in fact, being as close to objective as one can be with issues that are not strictly factual (there being no empirical, quantitative method that I know of for measuring the level of (in)explicability of any person, place, thing, event or concept). But note: In her preface to the American edition of ES&L, Ms. Truss herself writes:

ES&L’s popularity is all the more perplexing because the book, whose “rallying cry” is “’Sticklers unite!’”, gets so much wrong. Not just about punctuation specifically but about grammar in general. Take, for example, the book’s subtitle: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. Eats, Shoots & Leaves most assuredly does not advocate a zero-tolerance approach to punctuation. Quite the contrary: It is massively in favor of punctuation—specifically, what the author deems (often erroneously) correct punctuation. Truss’s “zero-tolerance policy” is toward punctuation abuse or misuse and, although it's obvious that that's what's meant by the subtitle, it is equally obvious that that's not what the subtitle says. (It is easy enough to read an author’s words, but it is a bit much to be required to read an author’s mind to properly comprehend those words.) In addition: “Zero Tolerance”, as employed in the subtitle, should be hyphenated. Ironic solecisms such as these abound in Truss’s tome, but managing to have three glaring grammar errors on the cover of a book extolling good punctuation has got to be a record—or so one would hope. The author of a book on correct punctuation should be able to stickle better than this—avoiding such rudimentary grammar errors should have been covered in, like, Stickling 101: The Art of the Stickle.

These criticisms may seem picayune or mean-spirited—C’mon! I can fairly hear the more grammatically-lenient among you saying (accompanied by a Can-you-believe-this-guy? eyeroll): You straight-up admit you know what Truss meant!—but I maintain that they are warranted. Bear with me as I unspool the reasoning behind my contention:

Not long after reading ES&L, I ran across Louis Menand’s critical review of the book in The New Yorker, which I quote at length below because his evisceration of Truss’s presumed expertise makes my critical observations above seem, comparatively, almost quaintly complimentary:

She is correcting an error on a public sign; but why should we trust that her “correction” is valid when a writer at The New Yorker itself has just told us that her claim that The New Yorker renders “the nineteen-eighties” as “the 1980’s” is just factually wrong?

It is not lost on me that the jacket image is meant to be humorous. But I would be more inclined to indulge that humor if the author were a bit more rigorous in vetting and proofing her own grammar and punctuation. As her author’s picture implies, Truss presumes to loom over others’ solecisms, Sharpie at the ready, prepared to correct perceived errors, tongue clucking judgmentally; I cannot help but cheer Menand on when, in his review, he looms equally judgmentally over Truss’s errors of the very same type while clucking his tongue at her. Plus I am a dead sucker for irony; and the fact that ES&L could stand as an object lesson in bad grammar and punctuation tickles my ironybone no end. Granted, quite a few rules of grammar can be said to be arbitrary, little more than a matter of preference (more on this below), so, um, who cares, right? But facts are facts and Truss gets quite a few of them out-and-out wrong, as well.

But it's not my intent merely to throw shade at Truss’s book (anymore) or to imply that I'm even more of a grammatical stickler than she; or, conversely, to imply that grammar and punctuation are not worth doing correctly. Examples of how they matter abound. This one illustration should suffice to make my point: “In 1872, one misplaced comma in a tariff law cost American taxpayers more than $2 million, or $38,350,000 in today’s dollars.” Long story short, in case you don't want to click through to the linked article for the full story: This tariff law listed items to be exempted from taxation under it; but instead of (correctly) exempting “[f]ruit-plants, tropical and semi-tropical for the purpose of propagation or cultivation” it exempted “[f]ruit, plants, tropical and semi-tropical ….” Biiiig difference. The law was intended to exempt tropical and semi-tropical fruit-plants; instead, it exempted tropical and semi-tropical plants of all kind, as well as tropical and semi-tropical fruits of all kind. So … buh-bye $38+ million in tax revenue, thanks to the comma that should have been a hyphen.

Grammatical niceties can matter.

But …

… there are other supposedly hard-and-fast “rules” of grammar that “matter” only in the sense that tut-tutting grammarians claim they do. For example, split infinitives. Can I get anybody other than a Militant Grammarian (apologies to David Foster Wallace) to really care about them? (And if you spotted, and tut-tutted at, the split infinitive in the previous sentence, congratulations! You yourself just might qualify as a Militant Grammarian!) And don't even get Winston Churchill started on the whole never-end-a-sentence-with-a-preposition initiative because he will just tell you that is the kind of nonsense up with which he will not put except he probably never said (or wrote) that though it sure sounds like something that pickled old rapscallion would say!

There is no good reason to proscribe ending a sentence with a preposition; in fact, laboring to avoid such an ending can lead to tortured syntax, which, while technically not a violation of the Geneva Conventions, sure ought to be. Churchill’s apocryphal “This is the kind of nonsense up with which I will not put” is a perfect example of a sentence so syntactically tortured that it should make your rhetoric gland ache.

Similarly, splitting an infinitive can clarify meaning and sound more natural; it's not hard to fully understand why that is so unless you are the type of person who thinks this sentence would have read better had I had written “fully to understand” back there a few words ago. Okay, granted, I could have written “to understand fully” without doing violence to the syntax; so let me moot this example instead: “If you want to understand—to really understand—why you might want to split an infinitive in a sentence, read this sentence rather than that first one I tried to sneak in as an example because that first one was less convincing and, frankly, kinda lame as exemplars go.” For good measure, here is an even more convincing example that will need no further defense or explanation (to those of a Certain Age): “To boldly go where noman Militant Grammarian has gone before.”

Boom. Mic drop. Star Trek FTW! Split infinitives rule!

Then there are some grammar rules that “matter” but not really, or maybe just not always, because you pretty much know what the speaker is trying to say even if s/he is not quite nailing it grammatically:

Great song, “If I Fell”! But when John and Paul harmonize

that last line is, technically, asking for the young woman being addressed in the song to guarantee she will love the male narrator more than she does some other unspecified female, which is clearly not what is meant. The line should be: “That you would love me more than she [did]”—“she” being, presumably, the narrator’s previous girl, who dumped him and broke his heart. But only a churl or a pedant would point that out because the change would diminish the song and how do you improve on a perfect love song anyway? A: You don't. (Also? Don't answer rhetorical questions. It's gauche.)

Why am I so lenient with the Beatles' "mistake" and so harsh with Truss's? 1: What the Beatles mean in the song is pretty obvious, despite the bad grammar. 2: They are making no attempt to set themselves up as arbiters of "correct" grammar.

Speaking of rules that sometimes matter and sometimes don't … I want to address a special case of pronoun agreement. Now usually, I'm straight up in favor of making pronouns agree in number, which I do in that sentence above that starts “Then there are some grammar rules that ‘matter’ …”. But that agreement sometimes comes at a cost; in the case of the sentence above, the cost is my use of the egregious “s/he” to make my pronoun agree with its antecedent “the speaker”, which is singular. I had to make a choice: does “the speaker” become “he” and thereby expose me to legitimate accusations of assumptions of male primacy? But calling “the speaker” “she” is equally gendered and, despite what some might argue, not much of a step toward toppling the citadel of patriarchal privilege. The best solution (since I'm of the opinion that gender-neutral suggestions like “ze”, “zir” and “zhe” have zero chance of catching on) is to do what most foax do in regular speech, which is to turn “the speaker” into “they” because, hey, no gender there! Problem is … “they” is plural and does not agree in number with the singular “the speaker” and … even though I myself consider “they” the best solution in situations like this, I just can't do it. (This is reminiscent of language maven William Safire’s coming out in favor of “ain’t” (sort of); still, I doubt he himself used “ain’t” in everyday life, despite his own recommendation.) Which leaves me with the atrocity that is “s/he” whose only saving grace is that it's at least not as clunky as “she or he” … but good luck trying to use “s/he” in spoken communication because how do you pronounce that? Really, I just wish I could get myself to use the “incorrect” “they” in these situations but, again, I just … can't. Yet I applaud those who do. As long as they are aware of its “wrongness”.

This next part may seem as though it is careening off topic and well into the weeds but bear with me …

Let us say your friend Ruttiger innocently enough avers: “All I did was inform Joe that the board members had rejected his idea and, even though I'm not on the board myself and had nothing to do with the decision, he started screaming at me! He literally shot the messenger!”

A Literally Rager (me, e.g.) is someone who would begin to examine Ruttiger’s body, looking for any overt signs of bullet holes because anyone who has literally been shot would literally have to have bullet holes in his/her [why can't I just say their?] body; or at least have some scars, if this literal shooting had occurred at some remote time in the past and the wounds had already healed. But we Ragers know that very few (read: none) of these literal shootings ever literally happened. The cliché “he shot the messenger” is, almost by definition, not literally true, because it is hyperbole, and hyperbole is pretty much the opposite of literality. Similarly, Angry Joe’s head didn’t literally explode while he was screaming at, and literally (only not really) shooting, Ruttiger, the mere messenger, but it would not surprise me in the least if Ruttiger went on to say it literally did.

We Ragers are, well, enraged by this misuse of the word “literally”.

Note that any Rager worth his/her/their salt would be perfectly fine with: “I told Joe of the board’s decision and his head exploded and he screamed at me, content to shoot the messenger because, hey, that's Joe, all screamy and head-asplodey, amirite?” We Ragers have nothing against hyperbole, exaggeration or other colorful rhetorical devices and tropes. In fact we love them! I myself am perfectly fine with someone’s saying: “Joe’s head almost literally exploded!” because that “almost” acknowledges that nothing of the head-exploding sort, in fact, happened. But that “almost” is necessary to placate us Ragers because the thing about Ragers is we really, really like and respect the term “literally” and we are merely trying to keep it from being diluted.

To illustrate: In a world where “literally” was not abused, you could say:

and not have to worry that the conversation would continue thusly:

Your Interlocutor: Wow! So by that you mean Stalin sent the general to a gulag?

You [sighing]: No, I told you. He shot him! What exactly does “literally” mean to you?

Your Interlocutor: O, the same thing it means to everyone: It is just a generic intensifier—

You: It is no such thing! It has a very specific meaning—

[And this is where you get all screamy and head-asplodey because you are a Literally Rager and, hey, it's just what you do when you spot abuses of “literally”.]

In a world where the term “literally” was not abused no one would need to explain that what s/he [they!] just said literally happened did, indeed, happen—literally. As Liz Lemon would say about such a world: “I want to go to there.” Except I'm pretty sure that world will never exist.

But here's the thing: Even I, a Literally Rager, know that it doesn't matter if people, in casual conversation or informal writing, misuse the term “literally”; or, similarly, if they employ the useful phrase “begs the question” to mean “leads to the question” (for they're not the same); or if they claim that ray-ee-ayyyn on your wedding day is ironic. (It's not.) These are solecisms that I myself have, well, not exactly raged at, but made mental note of when I encounter them and have judgmentally shaken my head over. Okay, okay … I have, on occasion, raged at them. But I can't think of a single instance in which these “misuses” of language and grammar have made it impossible for me to grok what the people who used them meant. At worst, you might need to ask a follow-up question to get clarification, but sometimes you need to ask follow-ups on sentences that are cast perfectly grammatically. Pick a sentence, pert-near any sentence, from a late-career novel of Henry James; its impeccable grammar will not make it any easier to comprehend. The near-impenetrability of some of James’ sentences has not lessened the intensity of my appreciation for his novels.

My overall point here is, yes, knowing the rules of grammar can be helpful. One should make every effort to follow those rules when speaking or writing formally. If you're the kind of person who derives enjoyment, or even a sense of superiority, from being GC (Grammatically Correct) all of the time, no matter how casual the circumstances—have at it! Knock yourself out! But never lose sight of the fact that the point of language is to make yourself understood. Anyone who accomplishes that goal, whether grammatically or ungrammatically, is doing okay.

So if you're the type of person who stands at the ready to point out and correct others’ grammatical errors no matter how informal the setting, you might be a Grammar Fascist. A Grammar Fascist is different from a usage stickler or a language maven or just your run-of-the-mill Person Who Digs Grammar; the latter types just enjoy knowing and learning about grammar—and why not? It's fun! But Grammar Fascists insist that others buy into their fascination with and rigid adherence to the Rules of Grammar (or in Truss’s case, the Rules of Punctuation)—as though adherence to the rules were the point of communication. Those who don't adhere are considered inferior, ignorant, worthy of being corrected, mocked and shamed.

I'm sure I'm not the only one who believes that the only time it's enjoyable to witness someone else’s grammar choices being nitpicked is when the victim of the nitpicking is a self-appointed Guardian of Good Grammar, aka, a Grammar Fascist. As I said earlier: Live by that sword? Be prepared to die by it. Because no matter how Grammatical (or Fascist) you may be, you'll make a mistake.

And there will always be another Grammar “Expert” (or Fascist) around to point it out when you do.

Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen ed. by Mary Norris

The Curse of Diaeresis by Mary Norris Those two dots The NYer insists on putting over the second vowels in words like "coöperate" and "reëlect" may look like umlauts, but don't be fooled. The New Yorker's "Comma Queen" explains that they're not. And possibly the only reason the magazine still uses them is ... the guy who wanted to discontinue them died before he could issue his edict. Or was it ... murther? (Spoiler Alert: It was not. But The New Yorker's punctuation rules are weird.)

Grammar.com

Grammar Girl Podcast on Soundcloud

Grammar Girl: Quick and Dirty Tips Blog

Grammar Snobs Are Great Big Meanies: A Guide to Language for Fun and Spite by June Casagrande

Making a Point: The Persnickety Story of English Punctuation by David Crystal

Mortal Syntax: 101 Language Choices That Will Get You Clobbered by the Grammar Snobs—Even If You're Right by June Casagrande

The New Yorker: Comma Queen Video Series “Mary Norris on language in all its facets.”

Any of the numerous On Language compilations by William Safire.

Punctuation Plain and Simple by Edgar C. Alward

Spellbound DVD. “Follows the lives of eight young Americans who share one goal: to win the 1999 National Spelling Bee in Washington, D.C.”

“Tense Present” by David Foster Wallace in Harpers April 2001. (Also available as “Authority and American Usage” in Consider the Lobster, a collection of Wallace’s essays.)

Eats, Shoots & Leaves is the book’s official title, though it should be noted that its jacket (left) depicts a panda on a ladder assiduously painting over the titular comma while another panda (or the same one, moments later?) with a gun walks off, stage-left—a visual depiction of the comma-laden meaning of the title. That comma’s presence or absence matters for purposes of meaning-interpretation; and the difference in meaning between the comma-laden version of the phrase and the comma-free version serves as rationale for the existence of the book itself. Without the comma, the phrase might refer to the fact that a panda “eats [bamboo] shoots and [various types of tree and plant] leaves” while, with the comma, the title might be alluding to the fact that a panda with a gun does just about anything it wants, but, most relevantly to the book’s title, it “eats [perhaps some yummy bamboo], shoots [a gun, presumably, but let us Pollyanna-ishly assume it fires that gun harmlessly into the air to celebrate how yummy those bamboo shoots were] and [then] leaves [before, say, the panda cops arrive, ask what all the shooting's about and start indiscriminately tasering panda-folk].” Point is, the comma—that seemingly insignificant punctuation mark—makes a big difference in how to interpret that phrase. Bestsellers have been constructed around less earth-shattering insights, I suppose, but I can't think of any examples offhand, so maybe not.

O, and also? The subtitle on the book’s cover is followed by a GIANT RED EXCLAMATION POINT!, which, yeah, I have no idea what that's all about. Seems gratuitous, which is odd for a book whose whole premise is that accurate punctuation matters.

Why a book “aimed at the tiny minority of British people ‘who love punctuation and don’t like to see it mucked about with’” should become a bestseller in Britain, much less in America, was then, and remains today, difficult to fathom. But bestsell it did—on both sides of The Pond.

When I deem the book’s popularity “inexplicable”, I am not being cruel or judgmental or—Heaven forfend!—cruelly judgmental; I am, in fact, being as close to objective as one can be with issues that are not strictly factual (there being no empirical, quantitative method that I know of for measuring the level of (in)explicability of any person, place, thing, event or concept). But note: In her preface to the American edition of ES&L, Ms. Truss herself writes:

To be clear from the beginning: no one involved in the production of Eats, Shoots & Leaves expected the words “runaway” and “bestseller” would ever be associated with it, let alone upon the cover of an American edition. Had the Spirit of Christmas Bestsellers Yet to Come knocked at the rather modest front door of my small London publisher in the summer of 2003 […]The prolix Ms. Truss goes on at some length in that vein, essentially saying, in her circumlocutionarily British manner, that the book’s popularity was, yeah, inexplicable. So Truss and I are on the same page on this, though I think I make the point more pithily, supra. Though, again, not judgmentally. (I get plenty judgmental later on in this post, however, if judginess is your thing.)

ES&L’s popularity is all the more perplexing because the book, whose “rallying cry” is “’Sticklers unite!’”, gets so much wrong. Not just about punctuation specifically but about grammar in general. Take, for example, the book’s subtitle: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. Eats, Shoots & Leaves most assuredly does not advocate a zero-tolerance approach to punctuation. Quite the contrary: It is massively in favor of punctuation—specifically, what the author deems (often erroneously) correct punctuation. Truss’s “zero-tolerance policy” is toward punctuation abuse or misuse and, although it's obvious that that's what's meant by the subtitle, it is equally obvious that that's not what the subtitle says. (It is easy enough to read an author’s words, but it is a bit much to be required to read an author’s mind to properly comprehend those words.) In addition: “Zero Tolerance”, as employed in the subtitle, should be hyphenated. Ironic solecisms such as these abound in Truss’s tome, but managing to have three glaring grammar errors on the cover of a book extolling good punctuation has got to be a record—or so one would hope. The author of a book on correct punctuation should be able to stickle better than this—avoiding such rudimentary grammar errors should have been covered in, like, Stickling 101: The Art of the Stickle.

These criticisms may seem picayune or mean-spirited—C’mon! I can fairly hear the more grammatically-lenient among you saying (accompanied by a Can-you-believe-this-guy? eyeroll): You straight-up admit you know what Truss meant!—but I maintain that they are warranted. Bear with me as I unspool the reasoning behind my contention:

Not long after reading ES&L, I ran across Louis Menand’s critical review of the book in The New Yorker, which I quote at length below because his evisceration of Truss’s presumed expertise makes my critical observations above seem, comparatively, almost quaintly complimentary:

The first punctuation mistake in “Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation” […] appears in the dedication [The first punctuation mistakes are, in fact, on the cover; see above], where a nonrestrictive clause is not preceded by a comma. It is a wild ride downhill from there. “Eats, Shoots & Leaves” presents itself as a call to arms, in a world spinning rapidly into subliteracy, by a hip yet unapologetic curmudgeon, a stickler for the rules of writing. But it’s hard to fend off the suspicion that the whole thing might be a hoax.

The foreword, by Frank McCourt, contains another comma-free nonrestrictive clause (“I feel no such sympathy for the manager of my local supermarket who must have a cellarful of apostrophes he doesn’t know what to do with”) and a superfluous ellipsis. The preface, by Truss, includes a misplaced apostrophe (“printers’ marks”) and two misused semicolons: one that separates unpunctuated items in a list and one that sets off a dependent clause. About half the semicolons in the rest of the book are either unnecessary or ungrammatical, and the comma is deployed as the mood strikes. Sometimes, phrases such as “of course” are set off by commas; sometimes, they are not. Doubtful, distracting, and unwarranted commas turn up in front of restrictive phrases (“Naturally we become timid about making our insights known, in such inhospitable conditions”), before correlative conjunctions (“Either this will ring bells for you, or it won’t”), and in prepositional phrases (“including biblical names, and any foreign name with an unpronounced final ‘s’ ”). Where you most expect punctuation, it may not show up at all: “You have to give initial capitals to the words Biro and Hoover otherwise you automatically get tedious letters from solicitors.”

Parentheses are used, wrongly, to add independent clauses to the ends of sentences: “I bought a copy of Eric Partridge’s Usage and Abusage and covered it in sticky-backed plastic so that it would last a lifetime (it has).” Citation form varies: one passage from the Bible is identified as “Luke, xxiii, 43” and another, a page later, as “Isaiah xl, 3.” The word “abuzz” is printed with a hyphen, which it does not have. We are informed that when a sentence ends with a quotation American usage always places the terminal punctuation inside the quotation marks, which is not so. (An American would not write “Who said ‘I cannot tell a lie?’ ”) […] And it is stated that The New Yorker, “that famously punctilious periodical,” renders “the nineteen-eighties” as the “1980’s,” which it does not.”And that's just the first three paragraphs. It goes on like that—a real smackdown, but worth reading in its entirety because it is more than a mere litany of Truss’s grammatical errors. The criticism is harsh but deserved. When an author sets herself up as an expert on a subject and then presumes to judge others on the basis of their deficiencies in this area of her alleged expertise, she had better be both correct in her assessment of them and not guilty of similar infractions herself. Or to express this idea in cliché form: If you live by that sword, be prepared to die by it. Truss, after all, opted to use this picture of herself on the inside book jacket:

She is correcting an error on a public sign; but why should we trust that her “correction” is valid when a writer at The New Yorker itself has just told us that her claim that The New Yorker renders “the nineteen-eighties” as “the 1980’s” is just factually wrong?

It is not lost on me that the jacket image is meant to be humorous. But I would be more inclined to indulge that humor if the author were a bit more rigorous in vetting and proofing her own grammar and punctuation. As her author’s picture implies, Truss presumes to loom over others’ solecisms, Sharpie at the ready, prepared to correct perceived errors, tongue clucking judgmentally; I cannot help but cheer Menand on when, in his review, he looms equally judgmentally over Truss’s errors of the very same type while clucking his tongue at her. Plus I am a dead sucker for irony; and the fact that ES&L could stand as an object lesson in bad grammar and punctuation tickles my ironybone no end. Granted, quite a few rules of grammar can be said to be arbitrary, little more than a matter of preference (more on this below), so, um, who cares, right? But facts are facts and Truss gets quite a few of them out-and-out wrong, as well.

But it's not my intent merely to throw shade at Truss’s book (anymore) or to imply that I'm even more of a grammatical stickler than she; or, conversely, to imply that grammar and punctuation are not worth doing correctly. Examples of how they matter abound. This one illustration should suffice to make my point: “In 1872, one misplaced comma in a tariff law cost American taxpayers more than $2 million, or $38,350,000 in today’s dollars.” Long story short, in case you don't want to click through to the linked article for the full story: This tariff law listed items to be exempted from taxation under it; but instead of (correctly) exempting “[f]ruit-plants, tropical and semi-tropical for the purpose of propagation or cultivation” it exempted “[f]ruit, plants, tropical and semi-tropical ….” Biiiig difference. The law was intended to exempt tropical and semi-tropical fruit-plants; instead, it exempted tropical and semi-tropical plants of all kind, as well as tropical and semi-tropical fruits of all kind. So … buh-bye $38+ million in tax revenue, thanks to the comma that should have been a hyphen.

Grammatical niceties can matter.

But …

… there are other supposedly hard-and-fast “rules” of grammar that “matter” only in the sense that tut-tutting grammarians claim they do. For example, split infinitives. Can I get anybody other than a Militant Grammarian (apologies to David Foster Wallace) to really care about them? (And if you spotted, and tut-tutted at, the split infinitive in the previous sentence, congratulations! You yourself just might qualify as a Militant Grammarian!) And don't even get Winston Churchill started on the whole never-end-a-sentence-with-a-preposition initiative because he will just tell you that is the kind of nonsense up with which he will not put except he probably never said (or wrote) that though it sure sounds like something that pickled old rapscallion would say!

There is no good reason to proscribe ending a sentence with a preposition; in fact, laboring to avoid such an ending can lead to tortured syntax, which, while technically not a violation of the Geneva Conventions, sure ought to be. Churchill’s apocryphal “This is the kind of nonsense up with which I will not put” is a perfect example of a sentence so syntactically tortured that it should make your rhetoric gland ache.

Similarly, splitting an infinitive can clarify meaning and sound more natural; it's not hard to fully understand why that is so unless you are the type of person who thinks this sentence would have read better had I had written “fully to understand” back there a few words ago. Okay, granted, I could have written “to understand fully” without doing violence to the syntax; so let me moot this example instead: “If you want to understand—to really understand—why you might want to split an infinitive in a sentence, read this sentence rather than that first one I tried to sneak in as an example because that first one was less convincing and, frankly, kinda lame as exemplars go.” For good measure, here is an even more convincing example that will need no further defense or explanation (to those of a Certain Age): “To boldly go where no

Boom. Mic drop. Star Trek FTW! Split infinitives rule!

Then there are some grammar rules that “matter” but not really, or maybe just not always, because you pretty much know what the speaker is trying to say even if s/he is not quite nailing it grammatically:

Great song, “If I Fell”! But when John and Paul harmonize

If I give my heart to you

I must be sure

From the very start

That you

Would love me more than her

that last line is, technically, asking for the young woman being addressed in the song to guarantee she will love the male narrator more than she does some other unspecified female, which is clearly not what is meant. The line should be: “That you would love me more than she [did]”—“she” being, presumably, the narrator’s previous girl, who dumped him and broke his heart. But only a churl or a pedant would point that out because the change would diminish the song and how do you improve on a perfect love song anyway? A: You don't. (Also? Don't answer rhetorical questions. It's gauche.)

Why am I so lenient with the Beatles' "mistake" and so harsh with Truss's? 1: What the Beatles mean in the song is pretty obvious, despite the bad grammar. 2: They are making no attempt to set themselves up as arbiters of "correct" grammar.

Speaking of rules that sometimes matter and sometimes don't … I want to address a special case of pronoun agreement. Now usually, I'm straight up in favor of making pronouns agree in number, which I do in that sentence above that starts “Then there are some grammar rules that ‘matter’ …”. But that agreement sometimes comes at a cost; in the case of the sentence above, the cost is my use of the egregious “s/he” to make my pronoun agree with its antecedent “the speaker”, which is singular. I had to make a choice: does “the speaker” become “he” and thereby expose me to legitimate accusations of assumptions of male primacy? But calling “the speaker” “she” is equally gendered and, despite what some might argue, not much of a step toward toppling the citadel of patriarchal privilege. The best solution (since I'm of the opinion that gender-neutral suggestions like “ze”, “zir” and “zhe” have zero chance of catching on) is to do what most foax do in regular speech, which is to turn “the speaker” into “they” because, hey, no gender there! Problem is … “they” is plural and does not agree in number with the singular “the speaker” and … even though I myself consider “they” the best solution in situations like this, I just can't do it. (This is reminiscent of language maven William Safire’s coming out in favor of “ain’t” (sort of); still, I doubt he himself used “ain’t” in everyday life, despite his own recommendation.) Which leaves me with the atrocity that is “s/he” whose only saving grace is that it's at least not as clunky as “she or he” … but good luck trying to use “s/he” in spoken communication because how do you pronounce that? Really, I just wish I could get myself to use the “incorrect” “they” in these situations but, again, I just … can't. Yet I applaud those who do. As long as they are aware of its “wrongness”.

This next part may seem as though it is careening off topic and well into the weeds but bear with me …

Let us say your friend Ruttiger innocently enough avers: “All I did was inform Joe that the board members had rejected his idea and, even though I'm not on the board myself and had nothing to do with the decision, he started screaming at me! He literally shot the messenger!”

A Literally Rager (me, e.g.) is someone who would begin to examine Ruttiger’s body, looking for any overt signs of bullet holes because anyone who has literally been shot would literally have to have bullet holes in his/her [why can't I just say their?] body; or at least have some scars, if this literal shooting had occurred at some remote time in the past and the wounds had already healed. But we Ragers know that very few (read: none) of these literal shootings ever literally happened. The cliché “he shot the messenger” is, almost by definition, not literally true, because it is hyperbole, and hyperbole is pretty much the opposite of literality. Similarly, Angry Joe’s head didn’t literally explode while he was screaming at, and literally (only not really) shooting, Ruttiger, the mere messenger, but it would not surprise me in the least if Ruttiger went on to say it literally did.

We Ragers are, well, enraged by this misuse of the word “literally”.

Note that any Rager worth his/her/their salt would be perfectly fine with: “I told Joe of the board’s decision and his head exploded and he screamed at me, content to shoot the messenger because, hey, that's Joe, all screamy and head-asplodey, amirite?” We Ragers have nothing against hyperbole, exaggeration or other colorful rhetorical devices and tropes. In fact we love them! I myself am perfectly fine with someone’s saying: “Joe’s head almost literally exploded!” because that “almost” acknowledges that nothing of the head-exploding sort, in fact, happened. But that “almost” is necessary to placate us Ragers because the thing about Ragers is we really, really like and respect the term “literally” and we are merely trying to keep it from being diluted.

To illustrate: In a world where “literally” was not abused, you could say:

The General conveyed the message to Comrade Stalin that the Enemy of the State had evaded Stalin’s secret police and so Stalin literally shot the messenger

and not have to worry that the conversation would continue thusly:

Your Interlocutor: Wow! So by that you mean Stalin sent the general to a gulag?

You [sighing]: No, I told you. He shot him! What exactly does “literally” mean to you?

Your Interlocutor: O, the same thing it means to everyone: It is just a generic intensifier—

You: It is no such thing! It has a very specific meaning—

[And this is where you get all screamy and head-asplodey because you are a Literally Rager and, hey, it's just what you do when you spot abuses of “literally”.]

In a world where the term “literally” was not abused no one would need to explain that what s/he [they!] just said literally happened did, indeed, happen—literally. As Liz Lemon would say about such a world: “I want to go to there.” Except I'm pretty sure that world will never exist.

But here's the thing: Even I, a Literally Rager, know that it doesn't matter if people, in casual conversation or informal writing, misuse the term “literally”; or, similarly, if they employ the useful phrase “begs the question” to mean “leads to the question” (for they're not the same); or if they claim that ray-ee-ayyyn on your wedding day is ironic. (It's not.) These are solecisms that I myself have, well, not exactly raged at, but made mental note of when I encounter them and have judgmentally shaken my head over. Okay, okay … I have, on occasion, raged at them. But I can't think of a single instance in which these “misuses” of language and grammar have made it impossible for me to grok what the people who used them meant. At worst, you might need to ask a follow-up question to get clarification, but sometimes you need to ask follow-ups on sentences that are cast perfectly grammatically. Pick a sentence, pert-near any sentence, from a late-career novel of Henry James; its impeccable grammar will not make it any easier to comprehend. The near-impenetrability of some of James’ sentences has not lessened the intensity of my appreciation for his novels.

My overall point here is, yes, knowing the rules of grammar can be helpful. One should make every effort to follow those rules when speaking or writing formally. If you're the kind of person who derives enjoyment, or even a sense of superiority, from being GC (Grammatically Correct) all of the time, no matter how casual the circumstances—have at it! Knock yourself out! But never lose sight of the fact that the point of language is to make yourself understood. Anyone who accomplishes that goal, whether grammatically or ungrammatically, is doing okay.

So if you're the type of person who stands at the ready to point out and correct others’ grammatical errors no matter how informal the setting, you might be a Grammar Fascist. A Grammar Fascist is different from a usage stickler or a language maven or just your run-of-the-mill Person Who Digs Grammar; the latter types just enjoy knowing and learning about grammar—and why not? It's fun! But Grammar Fascists insist that others buy into their fascination with and rigid adherence to the Rules of Grammar (or in Truss’s case, the Rules of Punctuation)—as though adherence to the rules were the point of communication. Those who don't adhere are considered inferior, ignorant, worthy of being corrected, mocked and shamed.

I'm sure I'm not the only one who believes that the only time it's enjoyable to witness someone else’s grammar choices being nitpicked is when the victim of the nitpicking is a self-appointed Guardian of Good Grammar, aka, a Grammar Fascist. As I said earlier: Live by that sword? Be prepared to die by it. Because no matter how Grammatical (or Fascist) you may be, you'll make a mistake.

And there will always be another Grammar “Expert” (or Fascist) around to point it out when you do.

Selected Grammar-Related Books, Podcasts, Videos, Blogs, Etc.

The Allusionist PodcastBetween You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen ed. by Mary Norris

The Curse of Diaeresis by Mary Norris Those two dots The NYer insists on putting over the second vowels in words like "coöperate" and "reëlect" may look like umlauts, but don't be fooled. The New Yorker's "Comma Queen" explains that they're not. And possibly the only reason the magazine still uses them is ... the guy who wanted to discontinue them died before he could issue his edict. Or was it ... murther? (Spoiler Alert: It was not. But The New Yorker's punctuation rules are weird.)

Grammar.com

Grammar Girl Podcast on Soundcloud

Grammar Girl: Quick and Dirty Tips Blog

Grammar Snobs Are Great Big Meanies: A Guide to Language for Fun and Spite by June Casagrande

Making a Point: The Persnickety Story of English Punctuation by David Crystal

Mortal Syntax: 101 Language Choices That Will Get You Clobbered by the Grammar Snobs—Even If You're Right by June Casagrande

The New Yorker: Comma Queen Video Series “Mary Norris on language in all its facets.”

Any of the numerous On Language compilations by William Safire.

Punctuation Plain and Simple by Edgar C. Alward

Spellbound DVD. “Follows the lives of eight young Americans who share one goal: to win the 1999 National Spelling Bee in Washington, D.C.”

“Tense Present” by David Foster Wallace in Harpers April 2001. (Also available as “Authority and American Usage” in Consider the Lobster, a collection of Wallace’s essays.)

Some thoughts:

ReplyDelete- Ending a sentence with a preposition is (thank goodness) no longer grammar anathema.

- Splitting an infinitive is (thank goodness) no longer grammar anathema.

- Shouldn't it be "If I were to fall in love with you . . ."?

- Language changes and evolves, as do meanings of words, as does correct spelling. However, like climate change, which also happens on its own but has been horribly exacerbated by the recent actions of human beings, language change is evolving wayyyy too fast due to our current state of instant communication. So I make no apologies for fighting it. Evolution at its own pace is fine and good. Evolution because people don't understand that "with Mary and me" is wrong because "with" is a preposition and a preposition takes the objective case, is neither fine nor good. Well, it's OK in casual speech, but never in writing of any kind. Same with "its" vs. "it's" vs. (and I've seen this) "its'".

- Bad grammar may convey correct meaning, but like a mistuned note on a piano, it can be so jarring that it grabs the focus of the listener or reader and pretty much ruins the whole experience.