Star, Man - David Bowie: A Life (Dylan Jones)

According to Dylan Jones in David Bowie: A Life, When David Bowie died early in 2016, his death was more momentous than John Lennon’s. Bowie had achieved the pinnacle of worldwide celebrity, wealth, and cultural influence that was completely unforeseen to those who were there during his meteoric rise in the 1970s. I was living in London as an adolescent early in that decade, although I wasn’t as attuned to pop culture as many of my peers (due to my dislocation from being uprooted every year or two from different continents and regions). I was as gobsmacked as everyone in my generation by the appearance of Ziggy Stardust and his later permutations, and can confirm that after Bowie’s early television appearances, no-one at school could talk about anything else. Bowie was beyond outrageous, his emaciated androgyny garbed in what was actually high-fashion women’s wear. “High-water” trousers displaying thigh-high boots, his translucent chest on display in billowy blousons, and hair spiked bright orange. At this time in America, long hair was still considered rebellious, as were bell-bottoms and – yes - denim, and bohemian attire in general. Bowie blew everyone’s minds with his alien look and persona, not to mention his suggestion of homoeroticism at a time when being gay was only recently legal but still considered a sign of mental illness.

David Bowie: A Life was published not long after the singer’s death, and is a collection of individual recollections of him by not only people who figured prominently in his life, but also those who barely encountered him and still were left with an articulable perception. This haphazard and disordered format compels the reader to connect the dots on their own and trace a template of David Bowie as person and performer. It is an apposite construction, mirroring the multiple faces and images that Bowie presented to the world on stage and in his music, ever shape-shifting and chameleon-like. Bowie as reactionary litmus to not just artistic influences but cultural movement as a whole. In his “real life” Bowie had a schizophrenic brother who introduced him to jazz and beatnik culture and later succumbed to suicide. Bowie’s mother’s family included histories of psychosis as well as suicide, and Bowie feared following in their footsteps. Jones posits that Bowie’s unremitting artistic “shape-shifting” was an expression of his fears and an attempt to exorcise and avoid succumbing to insanity.

Jones’ pastiche biography spouts factoids that help outline Bowie in a pointillist way; as an adult, I’m fully cognizant of the labors behind developing a stage presence in contrast to my adolescent perception of Bowie as a god-like figure fully-formed at the outset. Among those who helped compose Bowie’s characters Ziggy Stardust and “plastic soul” incarnations were his wife Angela (Basset) Bowie, who dressed him in high-end women’s clothing, and fashion designer Kansai Yamamoto, catalyst behind Bowie’s radical hairstyle and some of his more outre apparel. For Bowie, realism was found in “outsides and appearances,” which is a very London kind of conceit. In my humble opinion, England has always been at the cutting edge of style and fashion trends which, although paralleled in the U.S., tend to be of longer duration and less pronounced. The famous image of him “fellating” his guitarist Mick Ronson was actually his efforts at playing the guitar with his teeth, a la Hendrix. It was shocking for its time yet embraced by his (straight) fans, who weren’t alienated. Fellow musician Pete Townshend of The Who cites that “we all thought all the cool people were gay.”

Thus Bowie’s gay image (which was so pronounced that it appeared way beyond “an image” at all) was a calculated one, designed to further market his “outrageousness,” never mind that he did actually engage in sex and relationships with men. I found this purported calculating disingenuous somehow, and had trouble navigating the concept of manipulating one’s sexual response in this way. Jones then offers that his sexual favors were offered according to how recipients could advance his career. On the other hand, esteemed Ur-groupie Cherry Vanilla offered that “women found Bowie sexy and made them feel sexy too,” and praised him as a role model for homosexuals in the early 70s, who were still fighting for recognition and acceptance in the media and elsewhere.

Ultimately, Jones’ collection of apercus will be more appreciated by those who were touched by Bowie and don’t require a narrative arc outlining his career. The description of him as a cultural social climber in the extreme and how he culled influences piecemeal from everyone who met his esthetic criteria doesn’t diminish the heft of his self-actualization, which juggernauted him to stardom, as he fully intended from the outset. Jones suggests that Bowie consciously made the decision to choose fame over spiritual achievement (in his youth, he purportedly considered monastic Buddhism as a “career”). The maladaptive family dynamics

that Bowie recognized as underlying his energies is a prime example of turning one’s greatest weaknesses into one’s greatest strengths, assuming that his achievements are worth emulating—and if you are able. As an early teenager seeking individuation and identity, I was intimidated by English youth emulating Bowie with bristling florid Ziggy haircuts and flamboyant accessories. But the youth in me was satisfied to learn that it was Bowie’s early visits to America that prompted the Ziggy Stardust player. He found the States “intoxicating… dangerous… free.” I harkened back to the Apollo lunar landing in 1969, on the heels Bowie’s hit “Space Oddity” released two weeks prior:

This is Ground Control to Major Tom

You've really made the grade

And the papers want to know whose shirts you wear

Now it's time to leave the capsule if you dare…

|

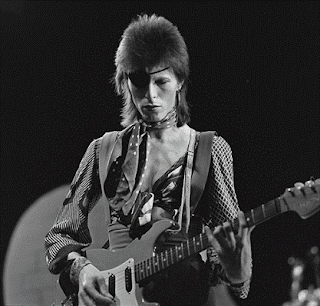

| Courtesy of TopPop |

David Bowie: A Life was published not long after the singer’s death, and is a collection of individual recollections of him by not only people who figured prominently in his life, but also those who barely encountered him and still were left with an articulable perception. This haphazard and disordered format compels the reader to connect the dots on their own and trace a template of David Bowie as person and performer. It is an apposite construction, mirroring the multiple faces and images that Bowie presented to the world on stage and in his music, ever shape-shifting and chameleon-like. Bowie as reactionary litmus to not just artistic influences but cultural movement as a whole. In his “real life” Bowie had a schizophrenic brother who introduced him to jazz and beatnik culture and later succumbed to suicide. Bowie’s mother’s family included histories of psychosis as well as suicide, and Bowie feared following in their footsteps. Jones posits that Bowie’s unremitting artistic “shape-shifting” was an expression of his fears and an attempt to exorcise and avoid succumbing to insanity.

|

| Courtesy of Hunter Desportes |

Jones’ pastiche biography spouts factoids that help outline Bowie in a pointillist way; as an adult, I’m fully cognizant of the labors behind developing a stage presence in contrast to my adolescent perception of Bowie as a god-like figure fully-formed at the outset. Among those who helped compose Bowie’s characters Ziggy Stardust and “plastic soul” incarnations were his wife Angela (Basset) Bowie, who dressed him in high-end women’s clothing, and fashion designer Kansai Yamamoto, catalyst behind Bowie’s radical hairstyle and some of his more outre apparel. For Bowie, realism was found in “outsides and appearances,” which is a very London kind of conceit. In my humble opinion, England has always been at the cutting edge of style and fashion trends which, although paralleled in the U.S., tend to be of longer duration and less pronounced. The famous image of him “fellating” his guitarist Mick Ronson was actually his efforts at playing the guitar with his teeth, a la Hendrix. It was shocking for its time yet embraced by his (straight) fans, who weren’t alienated. Fellow musician Pete Townshend of The Who cites that “we all thought all the cool people were gay.”

|

| Courtesy Wikimedia |

Ultimately, Jones’ collection of apercus will be more appreciated by those who were touched by Bowie and don’t require a narrative arc outlining his career. The description of him as a cultural social climber in the extreme and how he culled influences piecemeal from everyone who met his esthetic criteria doesn’t diminish the heft of his self-actualization, which juggernauted him to stardom, as he fully intended from the outset. Jones suggests that Bowie consciously made the decision to choose fame over spiritual achievement (in his youth, he purportedly considered monastic Buddhism as a “career”). The maladaptive family dynamics

that Bowie recognized as underlying his energies is a prime example of turning one’s greatest weaknesses into one’s greatest strengths, assuming that his achievements are worth emulating—and if you are able. As an early teenager seeking individuation and identity, I was intimidated by English youth emulating Bowie with bristling florid Ziggy haircuts and flamboyant accessories. But the youth in me was satisfied to learn that it was Bowie’s early visits to America that prompted the Ziggy Stardust player. He found the States “intoxicating… dangerous… free.” I harkened back to the Apollo lunar landing in 1969, on the heels Bowie’s hit “Space Oddity” released two weeks prior:

This is Ground Control to Major Tom

You've really made the grade

And the papers want to know whose shirts you wear

Now it's time to leave the capsule if you dare…

- Richard P., West Windsor Branch

Comments

Post a Comment