What is the point of fairy tales?

“Oh, how I love fairy tales.” So begins Kate Bernheimer’s “Fairy Tale is Form, Form is Fairy Tale.” The Rule of Three reading group at the West Windsor Branch read and discussed this essay in July, along with the story “Baba Iaga and the Pelican Child” by Joy Williams, and the poem “Little Red Riding Hood” by Matthew Zapruder. I adore fairy tales, but not everyone who participated in the discussion did. Of course, one of the things I enjoy in reading groups is when people disagree - it makes for an engaging conversation and challenges us all to articulate our ideas.

“What is the point of fairy tales?” someone in the group asked. “What are fairy tales for?”

As a fairy tale lover, I can think of so many answers to that question: fun, mischief, soothing a child to sleep, something to share while working with your hands, moral warnings, and hope. In the moment, I said: “Fairy tales are like folk songs. They are something shared and something familiar. They change a bit with each telling, the way a song sounds different depending on who sings it.” Just as the chorus or the bridge thrills and comforts, so does Snow White opening the door of the dwarves’ cottage to her wicked stepmother in disguise, and so do the words “Why grandmother, what big eyes you have.” Tales, like songs, are shared culture. In her essay, Bernhemier quotes Angela Carter:

“Ours is a highly individualized culture, with a great faith in the work of art as a unique one-off, and the artist as an original, a godlike and inspired creator of unique one-offs. But fairy tales are not like that, nor are their makers. Who first invented meatballs? In what country? Is there a definitive recipe for potato soup? Think in terms of the domestic arts. ‘This is how I make potato soup.’”

I find fairy tales as nourishing and delicious as my mother’s potato soup – and the soup comes out a bit differently when I make it.

Perhaps you do not like fairy tales – I do not mean to convince you. But if you are interested, or are curious (watch out! curiosity is both rewarded and punished in fairy tales), I have reading recommendations for you. Below, I’ve listed some collections of traditional tales, some contemporary retellings, and one excellent (and short) history.

The Original Folk & Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm translated and edited by Jack Zipes

In this volume, translated by the renowned fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes, you will find familiar tales like “Cinderella” along with some astonishing surprises. The book is filled with 156 stories and with new illustrations by Andrea Dezsö. Revisiting the Grimm tales is a great way to explore the tradition.

Italian Folktales by Italo Calvino

Calvino is one of my favorite authors, and here he turns his characteristic lightness and charm to retelling stories from across Italy. This collection of 200 tales is a joy, with some that feel familiar as they mirror other European tales, and some unique to Italy.

Wonder Tales edited by Marina Warner

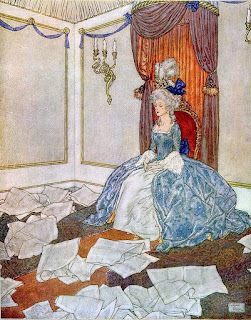

I recommend another book by Marina Warner below, but here she collects six French tales, each with a different translator, including John Ashbery and A. S. Byatt. While Grimm and Calvino tell tales collected from oral traditions, these are from the 17th century “literary” tradition. We know (mostly) the aristocratic authors of these tales from the reign of Louis XIV when conte de fées were all the rage at Parisian salons.

The Bloody Chamber by Angela Carter

Did Angela Carter begin the modern trend of retelling fairy tales? I’m not sure, but this influential collection remains a favorite. Her versions of “Puss in Boots,” “Bluebeard,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” and others are gothic, dark, and subversively feminist. In her telling of “Beauty and the Beast,” for example, the heroine turns into a beast herself to join her beloved in sensual monstrousness.

My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales edited by Kate Bernheimer

For more retellings of classic tales – and not just from the European tradition – I suggest this award-winning collection edited by Kate Bernheimer, founder and editor of the literary journal Fairy Tale Review. Each of the forty tales is inspired by a classic and are written by authors such as Joyce Carol Oates, Francine Prose, and Kevin Brockmeier. This collection includes “Baba Iaga and the Pelican Child” by Joy Williams, which my reading group universally adored.

Once Upon a Time: A Short History of Fairy Tale by Marina Warner

Marina Warner is an authority on myths and fairy tales, and this truly short (180 pages of text) introduction is excellent if you are interested in the history of fairy tales: who told them, who collected them, and how they have been interpreted and reimagined. As the publisher’s blurb says: “She makes a persuasive case for fairy tale as a crucial repository of human understanding and culture.”

I could suggest many more, but the books above are wonderful ways to begin. What are your favorite tales?

By the way, the Rule of Three reading group discusses three short pieces each month, all connected by a theme. In September, the theme is cities, and I invite you to join us.

- by Corina, West Windsor

Comments

Post a Comment